Mourning is a familiar experience. We have all cried at a funeral, visited graves, and sorrowfully reminisced with others. But perhaps these sorts of expressions are not as natural as they seem. In the Icelandic Egil’s Saga, for example, the death of his son Böðvarr drives Egil to lock himself in his room speechless for years until his daughter induces him to compose a memorial poem, which finally allows him to “move his tongue”. Today, we would probably call Egil “catatonic” and hospitalize him; in medieval Iceland, this was a normal reaction to death of a firstborn son.

At the other extreme, the sociologist Émile Durkheim noted the seemingly superficial reaction to death in certain Australian Aboriginal cultures:

If the relatives cry, lament, and beat themselves black and blue, the reason is not that they feel personally affected by the death of their kinsman…. If, at the very moment when the mourners seem most overcome by the pain, someone turns to them to talk about some secular interest, their faces and tone often change instantly, taking on a cheerful air, and they speak with all the gaiety in the world.1

At a contemporary funeral this would seem bizarre and disingenuous, but Durkheim emphasizes that this is completely normal behavior within those cultures: “mourning is not the natural response of a private sensibility hurt by a cruel loss… it is an obligation imposed by the group.”2

Indeed, even some of our seemingly most physiological responses have a cultural dimension. The Chukchee people of Russia, for example, perceive all foreign objects as “disgusting”, and whenever they see an unfamiliar object they experience a strong wave of nausea no different from that after eating spoiled food.3 We might not want to vomit, but many of us have similarly visceral reactions to certain kinds of music (death metal, perhaps?) or particular imagery in film.

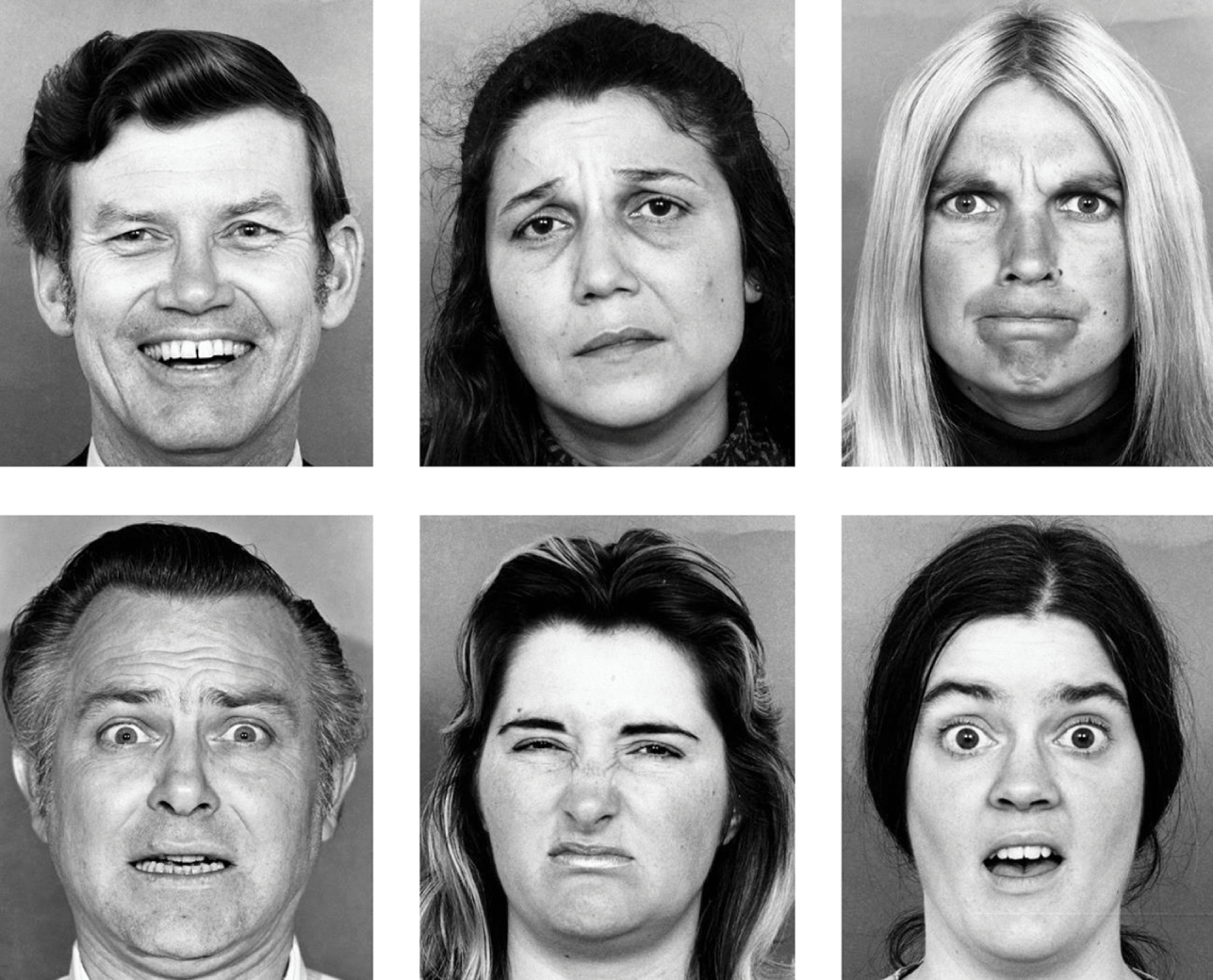

These experiences differ from how we normally think of emotions, as innate responses beyond arbitrary rules and customs. And there is significant evidence that there are in fact universal human emotions, expressed through culturally-independent patterns of behavior and facial expressions. Paul Ekman, for example, famously identified six of these: anger, disgust, happiness, sadness, fear, and surprise.4 Many of these are even shared with our nearest primate relatives, which would seem to make them unequivocally impervious to any human variation.

In fact, these universal emotions are so ingrained that they are often expressed and perceived outside of conscious awareness. They occur, for example, in the midst of everyday conversations and last for less than 500 milliseconds, with many shorter than 260 milliseconds— too short to be produced volitionally or perceived consciously.5 Rather, the flow of these “leaked” emotional expressions helps to generate what many would call the “vibe” or “tone” of an interaction, like the vague feeling that somebody is threatened, interested, or offended by something one is saying. We cannot consciously register them, but they covertly shape our behavior.

So what is the connection between these universal emotions and complex cultural behaviors like mourning? Are cultural expressions of emotion simply arbitrary practices with no relation to biological emotions, as Durkheim suggests? Or can we somehow link the two neurologically?

Ekman’s “universal emotions” are largely mediated by the limbic system, a group of structures deep in the brain. Normally, however, the limbic system does not operate on its own but sends much of its output to a distinctive part of the brain called the anterior cingulate cortex, or ACC. The ACC in turn projects to the frontal and parietal lobes, linking the limbic system to the complex behaviors of the human cortex which (unlike the behaviors induced directly the limbic system) are accessible to social feedback and conscious control. This means that an initial emotional trigger is essentially re-routed away from innate emotional expressions and toward more elaborate behaviors that can be shaped by social norms.

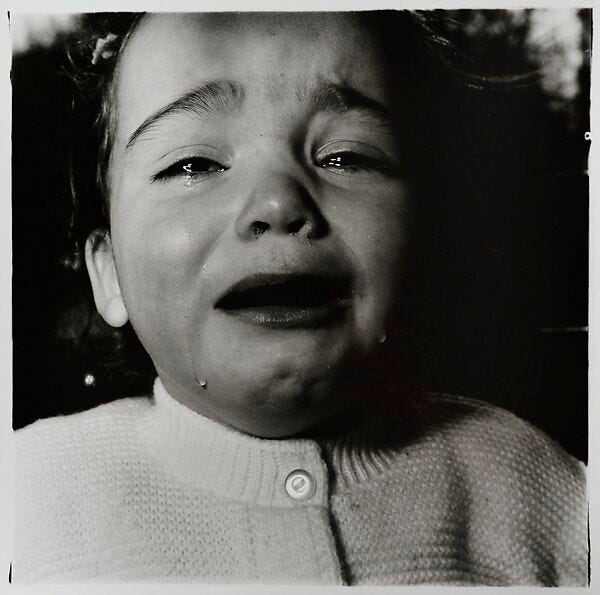

Perhaps the clearest example of this re-routing is human crying. In newborns, crying is a hard-wired response to distress that is generated by the periaqueductal gray, one of the most primitive components of the limbic system. Even anencephalic newborns— babies born without most of their brain — cry normally at birth due to an intact periaqueductal gray. Over the first years of infancy, however, the origin of crying shifts to the ACC, which changes the behavior itself.6 Crying becomes shorter, the infant actively seeks out its parents, and crying terminates as soon as the parents offer succor. In adults, crying is entirely generated by the ACC and neighboring medial prefrontal cortex, which transforms it into a completely social act: we can exaggerate crying for attention, suppress it when inappropriate, and replace overt crying with more subtle signals like sorrowful glances or protruding lower lips.

This transformation of crying also illustrates an important point about the cultural shaping of emotions. Traditional theories usually portray culture as simply inhibiting emotions: we are all born as expressive infants, and social life or “civilization” forces us to repress our native emotionality. This is the classic position of Sigmund Freud in Civilization and Its Discontents, for example, or of Norbert Elias in The Civilizing Process. Neurologically, however, this is wrong— the role of the ACC in emotional maturation is not to inhibit emotions, but rather to route their behavioral expression into culturally-learned patterns. The ACC acts as a behavioral switch, not a behavioral suppressor.

This is particularly evident in situations where culture dictates heightened, rather than suppressed, emotionality. The self-flagellation of the mourning rites described by Durkheim is perhaps the most dramatic expression of this, but there are many everyday instances. The sociologist Arlie Hochschild, for example, describes “emotional labor'“ in the service industry, or the requirement to display excessively friendly or positive emotions towards customers.7 A waiter greeting a diner with a bright “hello” and a broad smile at the end of a long shift or a car salesman gushing over the newest model are both artificially heightening their emotional expressions, and interestingly these sorts of deceptive expressions seem to strongly engage the ACC.89

The evolutionary evidence also supports the idea that culture transforms rather than suppresses our emotions. If we had evolved to suppress emotions, one would expect that there would be extensive inhibitory connections between the ACC and the more “primitive” limbic structures. While these connections exist, they are not strikingly different in human brains compared to those of other animals. Rather, the most dramatic difference in the human ACC is the expansion of a cell type called the von Economo neuron, named after the Austrian anatomist Constantin von Economo.10 Instead of inhibiting limbic centers, these neurons act to rapidly relay emotional information to sensory and motor regions of the cortex, allowing much more complex behavioral expression than the limbic circuits themselves.

Interestingly, destruction of von Economo neurons in the brain has been linked to many of the major neurologic disorders that affect social and emotional behavior. In frontotemporal dementia, for example, there is early loss of von Economo neurons in the ACC and the insular cortex.11 Unlike patients with Alzheimer disease, patients with frontotemporal dementia present not with memory loss but with highly inappropriate social behavior: laughing during serious conversations, throwing tantrums, and withdrawing from group activities. Similar loss of von Economo neurons has been found in autism12 and schizophrenia13. The problem in all of these disorders is not strictly disinhibition of emotion, but loss of culturally-learned modes of emotional expression.

Emotional experience is thus much more ancient than culture, but culture allows humans to express their emotions in extraordinarily varied forms. Central to this is the ACC, and especially its network of von Economo neurons that link basic emotions into complex, culturally-specific patterns of action. We may not grieve like Egil or slip into ecstatic trances, but we listen to break-up songs, chant at sports games, write eulogies, or simply give each other hugs. Even the smallest gestures depend upon the remarkable features of our ACC.

Durkheim, É. (1995). The Elementary Forms of Religious Life. New York: Free Press. p. 400

Ibid, p. 400

Bruner, J. S. (2009). Actual minds, possible worlds: Harvard university press.

Ekman, Paul. "Basic emotions." Handbook of cognition and emotion 98.45-60 (1999): 16.

Yan, Wen-Jing, et al. "How fast are the leaked facial expressions: The duration of micro-expressions." Journal of Nonverbal Behavior 37 (2013): 217-230.

Bylsma, Lauren M., Asmir Gračanin, and Ad JJM Vingerhoets. "The neurobiology of human crying." Clinical Autonomic Research 29 (2019): 63-73.

Hochschild, Arlie Russell (1983). The Managed Heart: The Commercialization of Human Feeling. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Lee, Tatia MC, et al. "Lie detection by functional magnetic resonance imaging." Human brain mapping 15.3 (2002): 157-164.

Ganis, Giorgio, et al. "Neural correlates of different types of deception: an fMRI investigation." Cerebral cortex 13.8 (2003): 830-836.

Allman, John M., et al. "The anterior cingulate cortex: the evolution of an interface between emotion and cognition." Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences 935.1 (2001): 107-117.

Seeley, William W., et al. "Early frontotemporal dementia targets neurons unique to apes and humans." Annals of Neurology: Official Journal of the American Neurological Association and the Child Neurology Society 60.6 (2006): 660-667.

Allman, John M., et al. "Intuition and autism: a possible role for Von Economo neurons." Trends in cognitive sciences 9.8 (2005): 367-373.

Brüne, Martin, et al. "Von Economo neuron density in the anterior cingulate cortex is reduced in early onset schizophrenia." Acta neuropathologica 119 (2010): 771-778.